Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the UK Labour Party seems… challenged? Both in the sense that it is being challenged, and the leadership challenge is itself challenged. Angela Eagle and Owen Jones are seeking to replace Mr. Corbyn, whilst the membership of the party seems to think Jeremy is a-okay in their books, and the Parliamentary Labour Party is just a bunch of self-interested jerks.

Yet it is fair to say that if you trust the polls, a Jeremy Corbyn-led Labour Party does not look like a sure winner should there be an election tomorrow. Now, let’s leave to one side the idea that either Eagle or Jones could turn that around (in part because to have that conversation, we have to discuss the sheer damage their camps are doing to the Party and its traditional support base, just in order to win a nominal election), and talk polls. Because polls are big business, and it seems that the common wisdom about polling is that they are no longer accurate.

Actually, let’s leave that to one side as well, because talk of the accuracy of polling is both boring, and terrible technical. As someone wise once said, there are lies, damn lies, and blogposts about statistical sampling techniques. No, let us focus our attention on this!

[H/T: Tom Freeman]

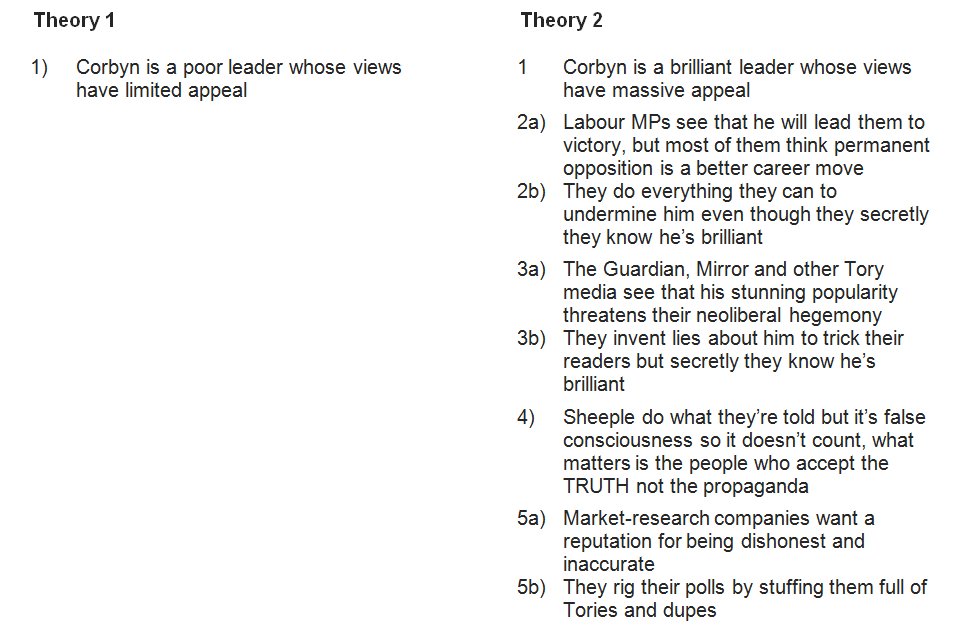

As the author of that image points out, ‘There are 2 possible explanations for Corbyn’s terrible poll ratings. It’s tricky, they both seem equally plausible.’

Yes, it’s the dilemma; is Corbyn just a bad leader who needs to be replaced, or is he opposed by vested interests. Depending on how you collect your evidence, one or the other (let’s just pretend the theses on offer are exhaustive and exclusive hypotheses), you will believe (or come to believe) one or the other.

How we gather evidence is important, but one thing that many people overlook (or just plain forget) is that our background beliefs inform how we both find new evidence, and how we interpret the evidence. The person who believes no one in their right mind would ever vote for a pacifist as PM will privilege (consciously or subconsciously) the evidence which confirms that hypothesis, whilst explaining away or ignoring evidence to the contrary. This is no pathology of reasoning which is the exclusive domain of any one group of reasoners; everybody does this, from poorly-paid philosophers, to the CEOs of Silicon Valley ventures. Evidence does not so much determine which theories to believe so much as theories determine what counts as actual evidence in a time and place.

I bring this up now to tell you what to think about poor Jeremy Corbyn and the UK Labour Party. Rather, I want to shuffle our attention to what happened in Turkey last week. Go read this.

Now, just in case you have a little short-term memory loss (because you’ve maybe had a drink or two, or you didn’t go click on that link…), the story is this: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan blamed Fethullah Gülen, a former compatriot who now lives in Pennsylvania, as being behind the military uprising in Turkey last week. Gülen, however, blames Erdoğan for the ‘purported coup’ in Turkey, claiming it could have been staged by the government.

False flag!

Now, as someone who has followed Turkish politics for a while now, I was perplexed by the coup. On one hand, Erdoğan seems like a bad ruler, one who is slowly dismantling a once liberal democracy founded on secular values, in order to carve out a place in the history books for himself. Erdoğan has expanded the powers of the president, reduced the political clout of the PM, sacked judges he doesn’t agree with, restricted the media, and so forth. He seems like a despot, and he’s even built himself a palace. On the other hand, military coups are bad, m’kay. ((I had similar perplexed feelings about the military coup in Fiji.))

So, what to make of the claim the coup was a false flag? It certainly seems possible; as sources in Turkey have pointed out, Erdoğan clamped down on the coup quickly and ruthlessly. He had a list of nearly three thousand coup linked judges that needed to be arrested at the ready, and another featuring over one and a half thousand military personnel. It all seemed a little convenient.

Or did it? Erdoğan knows he has enemies, and presumably keeps tabs on them. It’s not that unreasonable to think he’s been making a list of who’s naughty and nice (and checking it twice), and the aftermath of coup was simply the best time to make use of it. The fact Erdoğan was prepared to purge his enemies does not necessarily tell us much at all about the coup, but it does tell us something about Erdoğan’s ruthlessness.

Indeed, it’s in the interest of Hizmet (the rival political movement headed by Gülen) to ensure that the failure of the coup can be explained away with respect to Erdoğan’s known characteristics. Erdoğan has been reshaping Turkish political life for a while now, and what better to finalise that process than the reaction to a coup? Even if Gülen doesn’t really believe Erdoğan organised the coup, it makes sense for Hizmet to suggest it. It explains the failure of the coup (because it was never meant to succeed), allows Hizmet to distance itself from the coup and its leaders (since Hizmet opposes Erdoğan, so cannot really have been in on it), and it gives them another angle on just how bad Erdoğan really is.

So, from the perspective of someone who suspects Erdoğan of great ills, the idea he might have been the hidden hand behind the coup is an idea I’m happy to toy with. My prior judgements about his general character means I can see how this could be part of his plot to take sole charge of Turkey. Yet I’m not going to let my scepticism of Erdoğan’s good faith to overlook the PR benefits Gülen and Hizmet gain by suggesting Erdoğan might have organised the coup. Yes, it was convenient in the end to Erdoğan, because he has managed to purge elements opposing his reign in Turkey. Yet, if the coup was genuine, that was a predictable result nonetheless; you don’t typically get a second chance at a coup, something the conspirators would have known going in.